TICKLING THE DRAGON'S TAIL

Jake was just a tiny speck in a cobalt blue sky under this huge billowing white cloud with an ominous looking black bottom that appeared to be constantly churning, whipped into a frenzy, by some unforeseen force lurking in the heavens above the valley at West Rutland, Vermont. "I'm at sixty-six hundred MSL" (6,600 feet above mean sea level) Jake's voice crackled over the two meter radio, interrupted by static electricity building in that huge cotton ball exploding skyward above him. John handed me the binoculars and motioned toward the underside of the towering white cumulus cloud to the east of the launch site on the ridge. I focused on Jake’s tiny delta shaped wing, silhouetted against the roiling, almost yellowish-black background of the cloud bottom above him, and watched Jake circle upward in a tight spiral. "He’s got a lot of guts," I commented. "He can’t be more than three thousand feet below cloud base and that thing’s about to go cumulonimbus on him. How long’s he been in the air?" I handed the glasses back to John. "Less than fifteen minutes," he replied. "It’s colder than..." Jake’s voice was barely recognizable over the radio. His speech was disjoined and his breathing labored. It was obvious he had his hands full controlling the hang glider in what appeared to be fairly severe turbulence below cloud base. "What’s your climb rate," John asked Jake. "Don’t know," he replied after a brief pause. "The vario’s pegged at sixteen hundred." Jake was getting sucked upward at a rate in excess of sixteen hundred feet per minute. Pretty frightening to all but the most experienced and daring hang glider or paraglider pilots. Jake certainly fit that description with over twenty years of flying experience. "Something in excess of sixteen hundred feet per minute," John concluded. "I’d call that pretty unstable," I said. "Looks like some major cross country potential." I scanned the edges of the cloud for verga, wispy black vertical lines that indicate falling raindrops that never get to the ground. Verga will usually form at the edge of a towering cumulonimbus cloud reaching maturity. It indicates strong down drafts and severe turbulence, sometimes so strong it can literally tear a hang glider apart. "I don’t see any verga yet," I reported to John. "Do you think he’s alright?" "He’s the master of the mountain," John replied confidently. Jake continued to spiral upward under the cloud, tempting fate the higher he flew. I thought about the hang glider pilots they found in a field in France a few years ago, frozen solid, still strapped into the wreckage of their delicate hang gliders. They had frozen to death inside cumulonimbus monsters where temperatures can easily get below zero. Once the glider gets sucked up in the center of these weather engines, it can literally be impossible to get down. If you’re lucky, you get spit out the side of the column of rising air in the center, find a downdraft and escape the cloud with the glider still intact. If you’re not, you get spit out the top at 20,000 feet, plus, or the glider breaks up in the turbulence between up and down drafts. Of course, you still have a reserve parachute, but deployment can be quite tricky with the wreckage of the glider overhead, sometimes spinning. I took the radio from John. "What’s you’re altitude, Jake?" I asked him. There was a long silence as Jake fought the control bar to maintain the flying attitude of the glider. It looked like he went negative G’s a few times in what appeared to be more turbulent air closer to the bottom of the cloud. Finally he responded in short, successive bursts of the radio. "Getting a bit turbulent...Hard to control..." Labored breathing followed. "Can’t hold out much longer...Cold!" "It may be time to bug out," I suggested. Jake owned the mountain at West Rutland. He had been flying hang gliders there since 1973 and he held the site cross-country record at ninety-eight miles. I was the new kid on the block in no position to be telling the master how to fly. But I was concerned for his safety. "What’s your altitude now?" I asked him. Another long pause while Jake struggled to keep his weight under the wing. "Ninety seven hundred..." he replied finally. "That’s the record..." "I’ve seen him at eighty eight before," John said. "But I’ve never seen cloud base that high." Out west in the high desert, it is not uncommon to find cloud base at 16,000 to 18,000 feet above sea level, but in the east, clouds usually begin to form at 5,000 to 6,000 feet as the rising thermals forming the clouds reach the saturation point and moisture begins to precipitate out of the air, forming the white puffy clouds that often dot the sky in the summertime. The altitude of cloud base is the upper limit the glider can climb to (actually 500 feet below cloud base according to FAA regulations). It is illegal to fly in clouds and can be dangerous as the pilot loses his sense of what is up and what is down. "White out" conditions cut the pilot off from all ground references and can lead to a loss of control of the glider. Experienced pilots call it "flying in the white room". It can get downright scary in a cloud. The cloud can also contain severe turbulence, which is good to avoid, and no one wants to be hit by an airplane flying on instruments through the cloud. On unstable days, thermal lift has a tendency to be found under these white puffy clouds. The blue sky is generally a desert of lift where the sinking air returns groundward. To go cross-country, the glider pilot catches a thermal, which he or she takes up to cloud base by turning tight 360 degree turns until arriving just below cloud base, just like a hawk or other large bird of prey. Then the pilot hops from cloud to cloud in a downwind direction to achieve the maximum distance possible, "spending" altitude to cross the desert of descending air under the blue sky to the next lift column. Jake’s glider began to disappear into white whiffs of cotton at the bottom of the cloud. I watched him through the binoculars as he turned in a southeast direction and finally flew out from under the cloud. He had the control bar of the glider tucked down around his knees and accelerated very quickly through the more severe downdrafts at the edge of the cloud into the cobalt blue sky. "I’m outta here..." he informed us. Five minutes later, Jake disappeared over the horizon. Hans volunteered to chase him downwind on the ground. Like Pavlov’s dog, I was salivating to get in the air and follow him. Cross country at last! . . . I had been flying paragliders for three years at that time and I had only left the ridge at West Rutland once before. At twenty two hundred feet above launch, on the edge of an approaching warm front, I turned downwind and flew over the top of the ridge into the valley to the north. I followed the valley westward and landed six miles from where I had launched. There was no lift to be found anywhere once I left the ridge and flew out of the advancing edge of the warm front, so it had been a "sled ride" into the valley behind launch. Now, for the first time, I saw an opportunity to get high and go far. The adrenaline rushed through my arteries, my heart was beating much faster than normal, and my senses were on that keen edge of awareness that I would need to tickle the dragon’s tail under some large monstrous cumulus clouds. Surf’s up! We piled into the Cherokee and began the long bumpy climb up the backside of the ridge on the old washed out logging road we use to get to the launch site thirteen hundred fifty feet above the valley floor. I was so excited I could hardly contain myself. John accompanied me to launch, giving me tidbits of advice as we ascended. "It will be cold up there," John assured me. It was seventy degrees and sunny at launch. Everyone else was comfortable in T-shirts. I was roasting under a T-shirt, a sweatshirt, a sweater and a warm jacket as I spread out the paraglider canopy in a horseshoe shape behind the launch ramp. I put on my gloves and my helmet last. I attached the risers connecting my harness to the glider, activated the variometer, and assumed the alpine launch position facing the launch ramp with the risers draped over my arms, A-lines and brakes in my hands. I waited for some wind in my face. I waited and waited and waited, sweating in the warm sunshine dressed for much colder conditions aloft. It was so strange. No roaring thermals at launch. In fact, occasionally the air seemed to spill downward from behind me. I watched a hawk soar over two thousand feet straight up out in front of launch, so I knew there was lift in the valley, but without strong thermals blasting through the launch area, it would be difficult to inflate the paraglider and get into the air. High wispy clouds were swiftly headed eastward, but a large cumulus cloud was forming directly overhead at launch. I knew what I had to do. Find something going up in those light conditions out in the valley and then transition from the slope to the cumulus cloud overhead, get sucked upward to who knows how high, then turn downwind and go for the site cross-country record in a paraglider.

At last, I caught a slight upward cycle and pulled the glider up overhead into perhaps a 3 mph whiff of wind. I hit the launch ramp in a full gallop and looked up momentarily to check the paraglider canopy overhead. Everything looked fully inflated and ready to fly. I applied the brakes to just below ear level to prevent the glider from diving in front of me and charged down the ramp in a full sprint. The glider accelerated overhead and I lunged off the end of the ramp into the air like a lemming charging off a cliff.

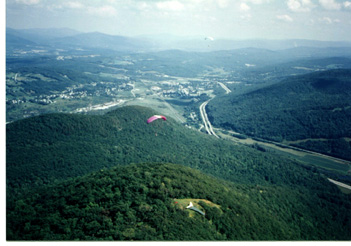

Air borne at last, I quickly checked the canopy overhead one more time and glanced at the vario. I wasn’t ascending, but I wasn’t losing altitude either. I settled back into my harness and got my feet up. I scanned the treetops below for any sign of a disturbance that would indicate the presence of a thermal turning leaves over as it progressed up the slope. I turned right and flew up the ridge listening for the variometer to tell me I was going up. Finally the vario came to life and I heard it beeping slowly as I entered a light thermal just to the west of the launch ramp. I applied both brakes simultaneously to slow the glider down and achieve "minimum sink", the slowest speed the glider will fly without stalling. I parked in this whiff of a thermal, almost motionless for perhaps nine or ten seconds, listening to the vario and watching the tree tops between my legs drop away slowly as I rose over the ridge. I caught a decent thermal there and circled in tight 360 degree turns until I found myself eight hundred feet over the ridge, over two thousand feet above the interstate highway on the valley floor below. Cars and trucks on the highway looked like toys between my legs. That’s when the cloud suck started. I was in an express elevator up - the vario pegged at its maximum reading, one thousand feet per minute. I ascended toward the yellow-black churning bottom of the cloud above. As the lift accelerated, I began to become concerned. I couldn’t see the top of the cloud to gauge its development. It can take less than half an hour for a friendly cumulus cloud to overdevelop into a cumulonimbus thundercloud and I was beginning to get concerned about the possibility of overdevelopment. The lift was smooth and I was not experiencing any significant turbulence, but the rate of my ascent was somewhat alarming. The ground was dropping away rapidly and West Rutland valley began to look like a surreal landscape painted on a very large canvas that I could poke through with my hand. The people on launch looked like ants and even one hundred foot trees looked like matchsticks.

I flew down the ridge to the east getting to over four thousand feet MSL by the time I flew over the launch site. I thought of the black churning bottom of the cloud above and what it would be like to get sucked up into the cloud. I thought of those French hang glider pilots and viewed my vario again. Still pegged at one thousand feet per minute. I couldn’t tell if I was ascending at twelve hundred feet per minute or two thousand, although I began to suspect it was closer to the latter reading. Rather than circling upward, I found it prudent to continue flying east toward the edge of the cloud. It got colder and colder the higher I went, which was a real relief at first. Normally the air cools about five or six degrees Fahrenheit with each one thousand feet of altitude. The greater the decrease in temperature with altitude, the greater the instability of the atmosphere and the greater the lift generally. Temperature loss on very unstable days can be as much as ten degrees per one thousand feet. The latter condition seemed to be the case as I rose higher and higher into colder and colder conditions. By the time I got to 5,000 feet it was below freezing. I was very glad I was dressed warmly. I knew I could do "big ears" if I was getting sucked up into the cloud, a

maneuver that the pilot initiates by pulling down the outside "A", or front,

lines of the glider, to fold up the wing tips and create a greater rate of descent. I had

practiced this maneuver many times in preparation for exactly this situation, but I

wasn’t sure big ears would get me down.

Walter Tripovitch, a local pilot who flew all over the world on his many business

trips, once described conditions he had encountered in Colorado near a large

overdeveloping cumulus cloud. He was a thousand feet above launch with a gaggle of other

pilots having a ball in thermal activity when a few larger clouds drifted by. Suddenly all

the paragliders were heading out to a landing. Walter’s guide instructed him to get

to the landing zone too because he was about to encounter great lift under the cloud. Walter started to the landing zone, but soon found himself in strong lift under the

cloud. His vario told him he was going up at a rate in excess of 900 feet per minute. He

pulled big ears to increase his descent rate. Now he was only going up at 400 feet per

minute. He began to worry. Fortunately, Walter was able to fly out of the lift and land

without incident. It’s possible to get into lift so strong that even big ears

won’t begin to create descent. If I wasn’t as lucky as Walter, the next maneuver would be a "B-line"

stall, in which the pilot pulls the B-lines, those attached about a quarter of the way

behind the leading edge, down approximately six inches. I had never practiced a B-line

stall and didn’t really feel comfortable performing it for the first time in these

conditions without any guidance from a qualified maneuvers instructor. I knew it was possible to get wild oscillations of the glider if the B lines are pulled

down too far. It’s also possible to go into a negative spin if the B lines are

released unevenly, and it’s possible to remain in a "deep stall" if the

lines are released too slowly. In a deep stall the glider descends like a parachute

instead of flying like a wing. The rate of descent is fast enough to break both legs on

landing. No, I wasn’t looking forward to experimenting with the B lines at that

point. And if the B line maneuver didn’t produce descent, the only trick left would be a

full stall, a very dangerous maneuver in which the back lines, attached to the rear of the

canopy, are pulled down below the seat, interrupting the air flow over the wing, creating

a plummet toward the ground. The canopy surges forward violently when the brakes are

released to "recover" from this maneuver, and it is entirely possible to be

looking over the trailing edge of the glider as it dives below you. It’s also

possible to fall into the canopy once it gets below you "recovering" from a full

stall. Joe Gluzinski, a California pilot and instructor tells a great story about flying a

high performance glider he was not too familiar with in fairly challenging conditions

somewhere out west. Somehow the glider surges over his head and actually gets below him.

Joe falls into the canopy and the canopy is flapping around his head, as he freefalls

toward the earth and certain death. Joe feels a bit disoriented without his vision, so he takes his helmet off to get the

glider out of the way, coolly deploys his reserve parachute and now has another wild

"there I was" story to impress his fellow pilots. I had never done a full stall

and wasn’t looking forward to it. I could see two smoke sources showing a wind out of the northwest. That explained the

lack of wind at launch. The launch ramp at West Rutland faces southwest. The wind had

actually been blowing over the top from behind me. I had launched into a "lee

side" thermal. Rather than circling upward any higher, I decided it was time to

follow Jake in a southeast direction. I kept climbing, higher and higher. The vario was screaming "up, up, up!" It

kept getting colder and colder. The digital readout on the vario hit 5,000 feet, then

5,500 feet, then 5,700 feet MSL. I was still four thousand feet below cloud base, but I

was higher than I had ever been before. To tell you the truth, I was scared. I didn’t

turn the glider in a spiral. I kept flying in a southeast direction. I had an ominous

feeling about the black bottom of the cloud. I had no interest in awakening a sleeping

dragon. Finally, I reached the edge of the cloud and flew out into the sunshine of the

cobalt blue sky. Suddenly the vario went silent. The glider surged forward momentarily. I applied the

brakes, slowing the surge, and brought the glider back overhead. Now the vario started to

whine out that sickening sound it makes when one is descending fairly rapidly. The digital

display read sixty two hundred feet. It was very cold. The whine increased in intensity to

a shrill pitch. I was descending at seven hundred fifty feet per minute in a downdraft at

the edge of the cloud. But I was feeling a lot better knowing I was headed back down into

familiar territory. It’s funny because all pilots know the higher we are, the safer

we are, because you have more time to react to an emergency, but for some unexplainable

reason, most pilots feel a lot more comfortable closer to the ground, below two thousand

feet, where we are much more accustomed to flying. I breathed a sigh of relief. After several minutes of fairly rapid descent, I found myself three thousand feet above

the ground and looking for another source of lift. Unfortunately, I had not planned my

departure from the first cloud very carefully and now found myself far from any other

cloud in the desert of sink in between the cumulus clouds that dotted the horizon. As they

say in the Indiana Jones film, "I chose poorly." I spotted some newly plowed farm fields in the direction of the Rutland Airport and

decided I had enough altitude to leave the superhighway directly below me where landing

fields were plentiful and skirt over a ridge containing only tall trees, a short cut to

the plowed fields where I hoped to discover more lift. The glider progressed at a snail’s pace over the ridge and I began to think about

the advantages of flying hang gliders where it is possible to get the glider up to eighty

miles per hour in a dive. It wouldn’t take long to cross that desert of lift out

under the blue sky in a hang glider and get to the next island of lift under those clouds

east of the airport, as Jake had done. But alas, I was flying a paraglider with a top

speed of only twenty miles per hour. It would be a very slow death indeed as I continued

to descend earthward. When I finally arrived at the black earth of the plowed fields below, I was a mere

fifteen hundred feet above the ground. Still high enough to catch a thermal and gain

altitude again, I thought. I searched desperately for lift registering a slight rise on my

vario several times. I turned tight 360-degree turns whenever the vario sniffed out the

slightest bubble of lift, but the thermals were too small and weak to take me aloft. I

followed a tractor, hoping it might trigger a thermal, but no such luck. The airport was still a good mile ahead, but I had to pick out a landing zone and set

up my landing. I rounded a farmhouse at a rural cross roads and turned into the wind for

final approach, landing next to a barn in what turned out to be a pasture recently

spread with manure. I quickly gathered up the glider. I had neglected to radio the others at launch while I was still in the air and had a

direct line of sight to the launch area. I could raise no one on the radio to arrange for

retrieval once I had landed. "Where am I?" I asked the farmer. I knew it wasn't Kansas.

"Clarendon," he said, with a smile. "How far from the airport?" I asked. "About a mile." I had covered over 10 miles in less than forty-five minutes, a new record for a

paraglider from West Rutland and my personal best. Jake went forty-five miles under his

hang glider that day and Jeff Nicolay went nine miles under a paraglider that day from

Ascutney Mountain on the Connecticut River in Vermont to Morningside Flight Park in

Claremont, New Hampshire. With my glider, harness and helmet neatly tucked away in my backpack, I hitch hiked

back to Jake’s house in the valley out in front of launch and celebrated with Jake,

Hans, John, Ruth and the others, with Budweisers. Once again our relationship with the hang glider pilots who had been flying the site

for twenty years had paid big dividends. If Jake hadn’t already been in the air to

report conditions, I’m not sure I would have launched. And even if I had launched, I

would not have dressed warmly, and would have found myself in conditions below freezing

dressed in a T-shirt.

In other parts of the country difficulties often broke out between hang glider and paraglider pilots when the latter emerged in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Many hang glider pilots resented sharing airspace with these "bag wings" at flying sites they had created. To say the least, paraglider pilots were often unwelcome. We were very appreciative of the valuable assistance of hang glider pilots at West Rutland. I often felt that I was standing on the shoulders of giants, the pioneers of ultra light gliders in Vermont, when I flew at West Rutland.

|