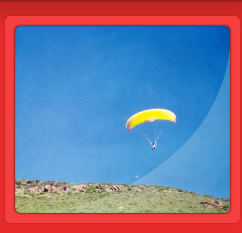

MAGIC MESAFloating over the rim of a 680 foot lava mesa, 30 miles north of Ensenada, in Baja, Mexico, in the company of several black ravens, I glanced to the west to take in the spectacular view of the sun setting over the Pacific Ocean. Below me, on top of the mesa, long horned cattle looked up in bewilderment at the yellow and pink wing over my head. I must have looked like an alien to them. The crinkling of the canopy momentarily dispersed them and they fled into the desert. I chased one of them briefly and then returned to the rim. One hundred feet below me, the steep walls of reddish-brown basalt protruded into the smooth, rising air currents that sustained my flight. I slowly progressed several miles to the end of the ridge, my turn point, briefly facing into the west wind before pointing south again. Aided by a fairly strong tail wind, I rushed southward with much greater speed. It had taken me fifteen minutes to reach the northern point of the mesa, but only four or five minutes to return to launch. Passing Walter under his massive pink canopy headed north, I could restrain myself no longer. I let out a yelp of joy as Walter floated by with a broad smile on his face. "It doesn't get any better than this," he yelled.

It was paragliding heaven and we were enjoying every second of it. We left the San Diego area in Ken Baier's van, headed down the Baja California coast for Ken's favorite ridge soaring mesa at noon, and arrived in La Salina at about one o'clock p.m. The wind in the landing zone was strong and almost due north, but Ken assured us that on top of the mesa it would be blowing in a more westerly direction. Ken pointed to the ravens soaring in front of the western face and announced that conditions were "soarable". With paragliding packs on our backs and Ken's dogs scurrying around us, we began the forty-five minute ascent to the top, through sage brush and cactus broken by rock out croppings. At the top of the rim, we turned south to a clear area with a rounded slope facing northwest into the wind. Walter quickly produced his electronic wind meter and stood at the edge of the precipice, watching its digital readout jump from 14 to 25 miles per hour. Too strong for us to launch, we waited on the ground, marveling at our jet black compatriots of the air soaring over our heads, teasing us with their playful dog fights, beckoning us to come join them. Pointing out a line of low clouds to the west over the ocean, Ken predicted that as the clouds approached us the wind would subside, but it was clear to us that we would have to wait several hours. "Ken rarely gets skunked," Walter assured me. "We'll see," I replied. It was a breathtaking view and I really didn't mind the wait. I thought of the snow fields covering the ground at home in Burlington, Vermont, and smiled in the warmth of the Mexican sun in March. Ken spent much of the time explaining local weather features that make this mesa soarable in onshore breezes most days. The lava field to the east is sparsely vegetated and heats up faster than the surrounding ground, sucking air in from the ocean to replace massive thermals as they lift off. "Unlike Torrey Pines (a world renowned coastal soaring site in San Diego), this place is uncrowded," Ken stated the obvious. "It is an ideal site for beginners to learn ridge soaring without contending with hoards of hang gliders, paragliders and sailplanes, squeezed into a narrow lift band."

As the afternoon wore on, the winds failed to subside much and we all became anxious to fly. But shortly after four p.m., the clouds finally blew in from the Pacific and shut off the thermal generator that was producing stronger gusts. Just as Ken had predicted, the winds began to abate. By five p.m. the maximum gusts were down to 17 m.p.h. and it was time for Ken to take a test flight as our "wind dummy". Ken inflated his canopy and struggled forward to the edge of the mesa. With a quick application of his brakes, he immediately ascended to 100 feet over launch and hovered over the mesa for a few minutes, testing the air for maximum gusts and "bumpiness". Satisfied that it was suitable for Walter and I to fly, Ken landed at the launch site and helped us into the air. I pulled my canopy up and it quickly surged overhead. Ken held me on the ground while I checked to make sure the paraglider was completely inflated. Satisfied, I spun around quickly and started advancing toward the edge. My feet left the ground, but Ken continued to tug me down and pull me forward. At just the right moment, he released me and I ascended to 100 feet over launch, inching forward in a northerly direction into the headwind. By the time I returned to the launch area, twenty minutes later, the winds were lighter and very smooth. I did tight "figure eights" over the launch area, rising and descending at will for about five minutes, and then, on a close pass over launch, I landed on top, my first top landing! With Ken's assistance, I was back in the air five minutes later and spent the remaining fifteen minutes of daylight hovering over the rim of the mesa in ever lighter winds. Finally, Ken warned me that it was time to head to the landing zone before it got dark. "Put on the headlights," I joked. "I'm not ready to come down yet." Walter headed out to the landing zone shortly after that and Ken was close behind him. I lingered over the edge of the rim, reluctant to give up the remaining lift to the ravens. Alone in the air, I made a final survey of the landscape below and watched Ken's dogs race down the slope to the landing zone. "It really doesn't get any better than this," I murmured. "This is truly magical." Finally, I descended below the rim and turned west into the bright red sky. By the time I touched down, it was twilight. We packed up our canopies and headed north to San Diego, savoring the memory of an exceptional ridge soaring day, leaving the magic mesa to the ravens, the cattle and the creatures of the Baja desert, until the next trip. |